Term Paper

December 15 2024

Phil 3301-Term Paper December 15 2024-

An essay I wrote in december of 2024 for my analytic philosophy-in origin class. This class preceeded my analytic philosophy-in progress class, which was a continuation of this class and can be seen in my John McDowell, and Jan Zwicky papers.

This essay was me trying to weave together a through line with honestly too many philosophers for one paper.

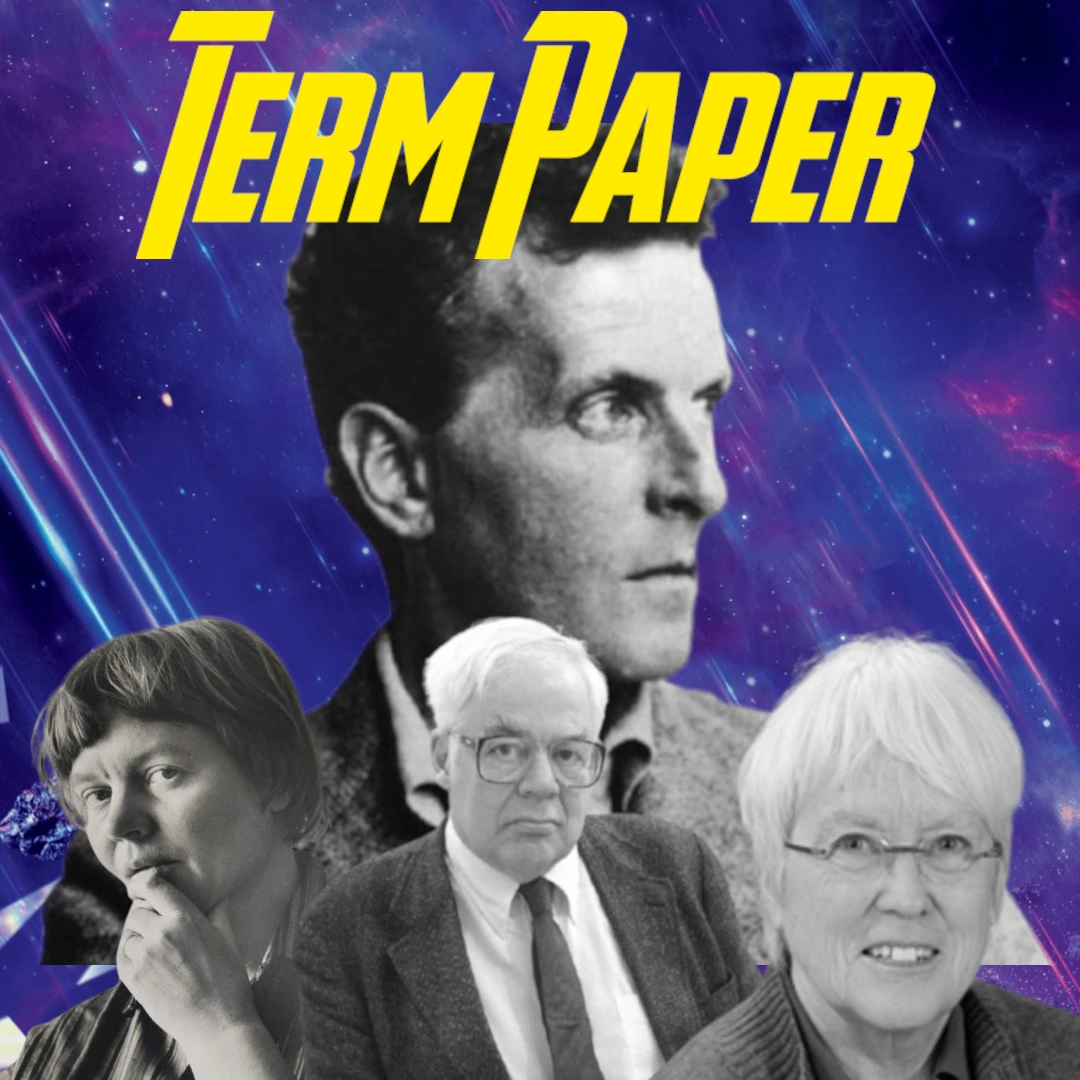

In this essay I cover early and late Wittgenstein, Richard Rorty, Iris Murdoch, and Lorraine Code. At the time, this was my

most comphrehensive essay, and I think it was an important step in my philosophy writing progress.

This class sort of taught me what writing philosophy is all about. I didn't come out a master, but

after going back to some earlier essays I wrote at the start of this class, they don't compare.

Peter MacAulay

PHIL 3301

Dr. Moser

15 December 2024

Term Paper

Early Ludwig Wittgenstein’s work in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, shows the logical structure of reality and how language mirrors it through propositions. Wittgenstein also attempts to show the readers the limits of language. Similarly, Iris Murdoch demonstrates how using metaphors grounded in human experience can greatly improve understanding of theoretical constructs. In Wittgenstein’s later Philosophical Investigations, he shifts his focus toward practical use and shared understanding of language. Richard Rorty’s pragmatic views share similarities with later Wittgenstein in showing us, the importance of context and utility in truth. In our world today, understanding is not only useful for philosophy, but it is also a vital step toward bridging human divides. Lorainne Code furthers Rorty’s views but questions what we can know and the responsibilities of knowing. She further shows that action in seeking knowing is crucial. Through understanding, we can determine our values, and then we can then act upon them. Understanding context is what can connect humans and progress society. Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, is a peculiar and deeply methodical philosophical work. Early in the text, it becomes clear that young Ludwig Wittgenstein is attempting to construct a precise framework that defines the world and the relationship between everything in it, and even what lies beyond it. He begins the book by saying, “The world is

everything that is the case” (Wittgenstein, 1, p57). From this foundation, Wittgenstein systematically defines his structure of the world. He proposes that the world is made up of facts rather than mere objects, for an object is unthinkable but facts can be thought and said through language and logical propositions. Wittgenstein's “picture theory of meaning,” suggests that propositions function as pictures, mirroring the logical structure they describe. Wittgenstein determines that language can describe the facts of the world through propositions, while logic shapes and structures what can be said. Wittgenstein says that everything beyond the world, such as philosophy, ethics, or the mystical cannot be described by language because they are topics that deal with what lies beyond the factual realm. Philosophical problems arise when we attempt to say what can only be shown.

In the second to last proposition of the Tractatus, Wittgenstein says, “My propositions are elucidatory in this way: he who understands me finally recognizes them as nonsense, when he has climbed out though them, on them, over them (He must so to speak throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it)* He must overcome these propositions; then he sees the world rightly*”(Wittgenstein, 6.54, p117). I believe that by saying that his propositions are nonsense, Wittgenstein is saying that his propositions attempt to describe beyond the world which he established is not possible for language. In the metaphor of the ladder, Wittgenstein is suggesting that the propositions aid in beginning to understand philosophical problems, but they cannot describe what is not of the world.

Wittgenstein tells the reader how the Tractatus will end in the preface by saying, “This book will perhaps only be understood by those who have themselves already thought the thoughts which are expressed in it —or have thought similar thoughts.” (Wittgenstein, Preface, p55). This passage tells the reader from the very beginning that the propositions are only useful to a point but after that, you will need something more akin to proposition 6.54. The ladder metaphor in proposition 6.54, appears very clear to the reader that Wittgenstein is saying the propositions can only take you this far, and you must use another way to adequately deal with philosophical problems. I believe in using a metaphor to tell this to the reader, he is suggesting that metaphors being grounded in human experience is what allows them to be more useful to understanding for the reader. A metaphor is a way to show philosophy because language is not conducive to describing what isn’t in the world, but the human mind is good at relating concepts to experience. Iris Murdoch speaks about the use of metaphors in her paper, ‘The Sovereignty of Good’. Murdoch says, “Metaphors are not merely peripheral decorations or even useful models, they are fundamental forms of our awareness of our condition: metaphors of space, metaphors of movement, metaphors of vision.” (Murdoch, p75). This quote shows how Murdoch views metaphors in a way that is not merely a tool in language but a way to view the human experience. A metaphor is a way to show a concept by reminding the reader how they might’ve felt in a given experience. A proposition may be able to describe the facts of the world as Wittgenstein showed. Wittgenstein also showed that those propositions are often very hard to grasp and understand. Metaphors as Murdoch describes, are very connected to how we think as humans. Metaphors communicate concepts in the same way that we think, this should help the receiver of the information be much more apt to understand it. Although we live in a world that is best described by propositions, we can acknowledge that as humans, we have learned to communicate differently based on our needs. While a proposition can deliver truth, the absolute truth is not always known.

Murdoch later in her paper describes unselfing. The process of unselfing requires the individual to let go of their personal biases, conflicts, and ego, to just reflect on the world. What is truly happening? She describes the need for unselfing by saying, ” We are anxiety-ridden animals. Our minds are continually active, fabricating an anxious, usually self-preoccupied, often falsifying veil which partially conceals the world. Our states of consciousness differ in quality, our fantasies and reveries are not trivial and unimportant, they are profoundly connected with our energies and our ability to choose and act.”(Murdoch, p82). The process is therapeutic to help the individual see what matters beyond their ego. Using metaphors Murdoch hopes to create a world in which concepts are easily digestible by describing them with shared experiences. Through frequent unselfing, she hopes to rid decisions of personal biases and remind people of what matters. This is a glimpse of pragmatic thought in that Murdoch does not want individuals to be bogged down by aspects that ultimately have no relevance in the situation. Murdoch is just offering it in a way to help the individual live morally and healthily. The overlap between Murdoch’s unselfing, and the thoughts of Richard Rorty, Lorainne Code, and even Wittgenstein is very interesting. While differing in their approaches, they are all working toward a common goal of understanding using relevant context.

In Wittgenstein’s next and only other published work, the Philosophical Investigations, he doesn’t quite pick up where he left but he does continue the work from the Tractatus with a new focus. This is why I believe he wanted the two works to be published together. The work in the Tractatus is so closely tied to the Philosophical Investigations as Wittgenstein guides you through everything to do with language. In the investigations, Wittgenstein pivots his point of determining the logical structure of reality and how language mirrors it through propositions and instead, he focuses on the use of language, ”The meaning of a word is its use in the language.” (Wittgenstein, §§43). When attempting to elevate a concept to find its meaning, you find that it can’t be done without using another definition. Wittgenstein gives the example of defining what a ‘game’ is to prove this point. He attempts to define what a ‘game’ is although every definition seems to lack the full expansion of what the word ‘game’ can mean. Thus, by attempting to put a definition on the word ‘game’ you are excluding aspects of the word. Yet we still know what people mean by the word ‘game’ and even more so when they put it in the context of what type of game they are referring to. Wittgenstein’s solution is to understand language through context. (Wittgenstein, §§66-77). A problem with language is that everyone can experience things differently. The solution is to acknowledge this fact and use human rationality to come to an understanding. Wittgenstein had a concept he called, a private language, in which a person’s experiences and perceptions result in a different private language for them, that is potentially incomprehensible to others. So how do we communicate if everyone has their own understanding that can vastly skew meaning between people? Rooting meaning in what you can agree on is how we generally are able to overcome the issue of different understanding. You can use what you both agree on and work from there. You could say that people could have such different perceptions to the point that agreeing doesn’t even mean the same thing or emotions work differently between the two people causing more confusion. This can happen but practically speaking these differences, while sometimes being hard obstacles to overcome, are just that, obstacles that can be overcome. Using language in this practical way we can more effectively communicate.

Wittgenstein introduces what he calls language games into the investigations. A language game is a simplified model of the world to understand better how we can understand and use language. Through language games, Wittgenstein was able to show how context is one of the most important aspects of language. A prominent example is that of the builders, A & B, who need to communicate to build a building despite not having a shared language, “B has to pass the stones, and that in the order in which A needs them. For this purpose they use a language consisting of the words "block", "pillar", "slab", "beam". A calls them out;—B brings the stone which he has learnt to bring at such-and-such a call.——Conceive this as a complete primitive language.”(Wittgenstein, §§2). Wittgenstein uses this example to show that through human reasoning, two builders who needed to communicate were able to do so using context. The example shows how it is not important for either builder to know more about the word other than it corresponds to a specific type of object. Despite there potentially being more than one block, or slab, the builders could understand that the name given was in reference to the type. This understanding is how humans learn to create language and use it. Language is for use and while definitions can help, they are only for context. A definition cannot be made without reference to something else, thus the definition can only be there to give context to your prior knowledge and experiences.

Richard Rorty, in his paper, ‘Pragmatism, Relativism, and Irrationalism’ champions the pragmatic view in showing that truth is adherent to context. Rorty shows us how truth is a tool that can be used to aid in understanding. We cannot know absolute truths because all concepts only have meaning in context. Wittgenstein showed this in the investigations with his critique of elevating concepts. Things are always changing in the world, even if we don’t know it. Why should we hold our truths to the standard of never changing; when the context changes, the utility of that truth is no longer relevant. Absolute truths are not something we can count on in the world, in regards to what the pragmatist wants, Rorty says, “He wants us to give up the notion that God, or evolution, or some other under-writer of our present world-picture, has programmed us as machines for accurate verbal picturing, and that philosophy brings selfknowledge by letting us read our own program”(Rorty, p726). In taking a pragmatic approach, you must do it with full intention of doing so. Rorty speaks on this by addressing the claims of him being a relativist and an irrationalist. To the claim of being a relativist, Rorty says that the definition of believing anything is not the ideology that he claims to be. Instead, he says that there are no truths or frameworks that are correct across all contexts. To address the claim of being an irrationalist, which would mean he rejects reason is also not what he believes. Rorty says that reason is crucial to developing contextual truths. To develop a truth, Rorty believes that you must use reason to determine the context of the situation you’re in, and from there you can determine a useful truth. A common critique of pragmatism is that it can be dangerous, but those claims are built on confusion of pragmatism with relativism, and irrationalism.

Rorty’s pragmatism is deeply entwined with the path that Wittgenstein has been going down throughout his philosophical career. Wittgenstein has been showing throughout his works that understanding each other is of utmost importance. More so in the investigations, Wittgenstein shows that context is key to that understanding. While Wittgenstein’s focus specifically on language is fascinating and deeply useful, Rorty’s pragmatism offers a wider approach with overall more utility. Rorty shows how language is for utility in determining truths, but he also shows the value of anti-foundationalism. As mentioned above in Rorty’s critique of relativism, he thinks that there is no truth or framework that can be true across all contexts and that is a key aspect to understanding our place in the world. By acknowledging this fact, you can begin to work with what you know. Rorty says, “The pragmatist, however, must remain ethnocentric and offer examples. He can only say: "undistorted" means employing our criteria of relevance, where we are the people who have read and pondered Plato, Newton, Kant, Marx, Darwin, Freud, Dewey, etc.” (Rorty, p736). Rorty’s Ethnocentrism is knowing what we know, because of where we are and the life we’ve lived. Rorty uses this concept because while he acknowledges that there are no absolute truths, you can use what has seemed to work throughout history given contexts. While Rorty says that ethnocentrism is useful in figuring out what you believe, you must also be open to new ideas and cultures. Rorty mainly uses ethnocentrism to advocate for Western liberal democratic values. He does this not because he believes that they are the only right values, instead he sees that they have worked throughout history, to foster inclusivity, reduce cruelty, and protect the freedoms of individuals. This is why Rorty believes that absolute truths for the sake of progress are nonsensical and useless. Rorty says, “The pragmatists tell us, what matters is our loyalty to other human beings clinging together against the dark, not our hope of getting things right.” (Rorty, p727) in this statement Rorty encapsulates what the goal of the pragmatist is, not to find truth but to aid humans. Having beliefs based on what is important and useful to us as humans, is allowing us to choose what we want to value. Rorty believes that we should all be ironic liberals. By this, he means that we should hold liberal values, but not rely on them or think that they can never lead us astray. Instead, Rorty urges us to question and evaluate our values, and knowledge based on context to garner a better understanding.

Lorraine Code in her paper, ‘What Can She Know’, goes over how knowledge is a social construct, and we need to reflect on what we can really know. The idea of a universal detached knower is impossible. This is because so many aspects affect a person and what they can know. For example, a person’s experience, identity, and place in the world, both physically, and structurally affect your ability to know. Code critiques the idea of objective knowledge entirely in saying that it leads to the dismissal of other views. This is like what we saw with Rorty in rejecting absolute truths because they can lead to a less useful answer given the context. Code takes a slightly different approach in describing her mitigated critical relativism, “to resist reductionism and to accommodate divergent perspectives”(Code, p320) she says this to highlight how many perspectives there are in the world, and so many of them are marginalized groups such as women who are overlooked and never considered. Thus, Code implores knowers to take epistemic responsibility. Such a responsibility states that a knower must always attempt to see what is beyond their own biases. As stated, Code believes knowing is social, and as such you must attempt to truly encompass as many views as you can to get the clearest answer. Knowledge after all is gained through social interaction as we do not have a use for knowledge beyond it. If you were to have someone who knew nothing, then they would not need to know, they only would need to feel and react. Knowing is a responsibility for living socially. To not take epistemic responsibility is to deny the existence of other groups in society and deny potential truth. While Rorty takes a passive position of suggesting we should be ironic liberals. So, to say that we should hold liberal values but be aware of pitfalls and be open to other ideologies is passive and leads to solidity in values but suggests no action. Code’s epistemic responsibility encourages knowers to seek out other views. Code is open to many different divergent perspectives but uses situational context to determine where we should search for answers. Code rejects forcing an answer by holding a belief so tightly that you are ignoring context and utility. Instead, by using situational awareness and previous knowledge, you can determine whether certain values are worth holding for the situation you’re in. This sounds very similar to Rorty but ultimately Code does not wish to push an ideology for it cannot be true in all situations. Although it may seem as though we have no knowledge now to help in determining future knowledge; we still have experiences and thoughts to rely on, but we just always have to address contextual aspects in determining answers. Prior thoughts and experiences are still there important, but the individual must always seek more perspectives and use that experience in the context of your situation. From early Wittgenstein, to Murdoch, to later Wittgenstein, to Rorty, to Code, all these philosophers have been about understanding something. As we went on it became more focused and clearer that understanding is key. Understanding requires context for a useful understanding, and it often requires various methods of aiding people to grasp that understanding. I believe that understanding is one of the most important parts of human society. Humans are always so divided based on differences in culture, education, and perceptions. Understanding each other is only the first step to closing rifts between people but it doesn’t end there. While understanding is a large first step in aiding humans, once that understanding is there, action needs to be taken. Action to not only ensure your understanding is useful but to do something now that we’re aligned. For philosophy, I see understanding as the goal and context as a means toward it. The question of what philosophy is has come up a lot over the term, and I think that the lack of definition is not surprising given the content of this course. A concept, even one so fundamental as philosophy which originates in ‘to think’, cannot be tied down to a single definition. In essence though, I think philosophy is to help humans. In saying that I don’t intend to have given any definition, but I think philosophy will continue to change as it has throughout history, but people will continue to try and figure out what is going on to aid progress. Ultimately, I think what philosophy comes down to is the context of the time, place, person, and many other factors. While philosophy can give us so much in understanding, the action is up to the people once they’ve united.

Works Cited

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Tractatus Logico-Philisophicus. Edited by Marc A Joseph, Broadview Editions, 2014.

- Murdoch, Iris. The Sovereignty of Good. Routledge and Kegan Paul. 1970

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. Translated by G.E.M Anscombe, Basil Blackwell Ltd, 1958.

- Rorty, Richard. “Pragmatism, Relativism, and Irrationalism.” Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, vol. 53, no. 6, 1980, pp. 717–38. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3131427. Accessed 15 Dec. 2024.

- Code, Lorraine. What Can She Know. Cornell University Press, 1991.