Theory of Forms By ME! (*IN PROGRESS*)

November 23 2025

- This is my first blog post, and honestly it isn't quite to the level that I wanted. Yet as this blog post discusses,

a foundation is important. This blog post is a about a theory that I've been working on mainly in my head

for the better part of two years. I needed to get some of it out in writing and release it somewhere. Even

if in a month from now I think and feel completely different about what I said in here, it will have

been worth it to get that foundation, not only for the theory to improve, but as my first blog post.

In this post I attempt to talk about Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Wittgenstein, Fanon, McDowell and Zwicky.

I forwarn you that I have not polished this and although I think it's somewhat readable, it's not finished.

Over the past two years I've had many thoughts about philosophy, but something that keeps coming back to me, is not exactly what we're talking about here, but it is what it evolved into. In a year or less from now I will likely have completely disavowed this theory entirely. I expect to overcome this theory just like the others I've had in the past. Although I felt that I've made some major progress over the last six-ish months and I want to make it into a solid foundation for what is to come. I am no longer satisfied to endlessly building theories in my head. I don't want to waste time rebuilding what is lost to the depths of my mind.

The theory I am speaking of spans philosophical history, and for that reason I will try my best to explain for both those who know some philosophical history and for those who don't.

To start at the relative beginning (although I do not believe it is the true beginning) we will start with Plato. In his many works Plato talks of forms. If you have not read about the forms before, they exist as primary aspects of existence that are to be followed to achieve harmony. Now quickly jumping to Aristotle, we have virtue. Immediately succeeding Plato Aristotle has similar themes and built out Plato's ideas to be more expansive. To live virtuously is to do something for it's own sake. To become virtuous you must cultivate virtue endlessly, similar to Plato's forms.

That last paragraph was to biggest oversimplification of Plato and Aristotle in history, but I felt any foundation for them is necessary for where we are going. Both Plato and Aristotle have discussed what I plan to talk about and generally have solved all the problems I seek to solve, but what is philosophy if not overexplaining the explained (I both wholeheartedly agree with that and disagree)

Now I wish to transport us to 18th century Prussia to discuss everyone's favourite German idealist, Kant. In his critique of pure reason, which I have not read (although I have read the Prolegomena to any future metaphysics which just explains the CPR), Kant gives us the baseline of what the world is, what it is not, what we can possibly know, and what we cannot. Read a Kant essay if you want the details, but essentially for Kant we live in the phenomenal world, our empirical world. Within the phenomenal world we can gather knowledge through intuitions from what our senses tell us about the world. This is our immediate reaction to the world. Over time those intuitions become concepts as a shortcut in your brain to recall multiple similar intuitions. An intuition of a single book you pick up could be red, smell musty, feel like leather, and taste dry, while the concept of a book may have certain characteristics associated with it based on how similar books you've encountered are, but ultimately it is just book. So what about what we cannot sense like time and space? Do they not exist? No, these are just pure intuitions, there is no denying that they exist but no particular sense is sensing them. Pure concepts on the other hand are ideas. Kant thinks all pure concepts fall into 12 categories. The specifics aren't very important here but what is important is that a pure concept is pure idea, it is not quite knowable but you still have a concept of it despite not being able to say you know it exists for sure, due to empirical experience. An example that Kant talks about a lot is cause. Cause is something that Hume would say doesn't really exist because how can we know it exists without just saying, well it always seems to happen this way so cause must exist. Hume resorts to scepticism which places us in a weird space of ambiguity, lost, disconnected from the world, cast away from society. This is where Kant says cause must exist because we do not want to live in this scepticism. He suggests that although we are unable to know pure concepts, we can think them. ideas exist in the realm of the noumena; we cannot know the noumena but our faith in its existence is what makes it real. Kant's transcendental idealism suggests that the phenomenal world is constructed my our minds based on principles of the noumena. This sounds a little crazy but I swear it kinda makes sense. It is due to this foundation that Kant is setting for the phenomena and the noumena that allows us to think that cause exists and keeps us from dogmatism where we take for granted cause and think we can experience it, while also keeping us from scepticism by giving us a place for cause. Now we have a foundation to build on.

Okay that was a lot, but I think Kant's foundation is genuinely helpful for fleshing out the issues we will later encounter and I always think that having any foundation is better than existing in pure ambiguity. Now that we have this foundation, the first thing I want to do is destroy it. As Kant's transcendental idealism suggests, everything that we just talked about is for us as people living in the world. The intricate weaving that Kant provided us with, giving us a somewhat satisfactory explanation of our reality is in my opinion just a story. Kant himself suggests this in his essay, 'Idea for a universal history with cosmopolitan intent' Kant describes history through the lens of nature having a plan for us because without that history lacks purpose and becomes stagnant with nothing to shoot towards. We need a story to grow. The noumena, as much as I might believe in it, is just a guiding star in the night. I have ideas of the world that exist in the noumena and I use those ideas as target to guide me in the phenomenal world. So when I said earlier that the phenomenal world is comprised of things we can know via possible experience, that was a story too. It is useful to us to say that anything we can experience is real knowledge. If this was not the case, we would fall into the same trap as before, scepticism would subsume us. It is useful to classify knowledge as things we can experience just as it is useful to create the noumena as a way to think about concepts that are unknowable but have affect on our life. If we get down to brass tax, the only thing we can know is that we cannot know anything. We live in ambiguity and everything we have is just a story we have built upon it. As discussed, living in pure ambiguity is not ideal. We are unable to do anything. We need structure not only for doing basic things like breathing, eating, walking, but also for interacting with people. In another of Kant's essays, 'What is Enlightenment' he discusses how only through interacting in society, we are able to gain any bit of enlightenment. In lawless freedom (a form of living in ambiguity) we are unable to grow, we do not have any tools to guide us towards anything. This is the same logic Kant is using in his universal history essay. Like leaf nodes in the tree of humanity we would have fruitless lives where no branches grow from us, only expanding horizontally on an endless horizon. While we don't necessarily want to live in ambiguity, we must acknowledge it's presence if we wish to understand what we are here for. More on this later.

I may change this ordering around later because I feel like you might need to know Wittgenstein, McDowell, Zwicky, maybe Fanon, maybe Merleau-Ponty, and maybe de Beauvoir, but I think that with this foundation of Kant we can get to my main point, my theory, and vision.

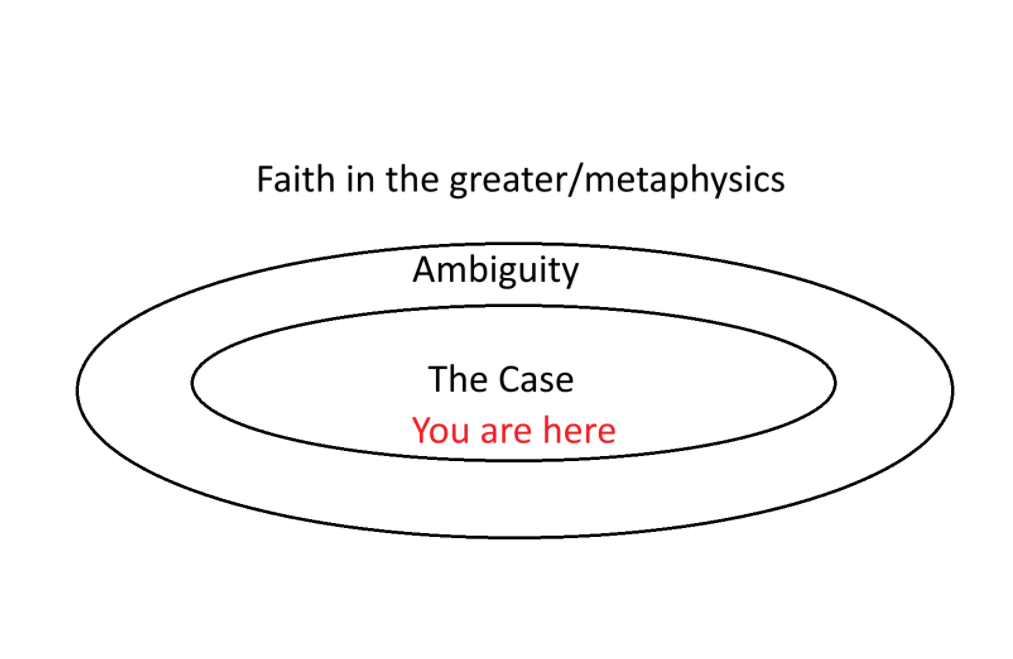

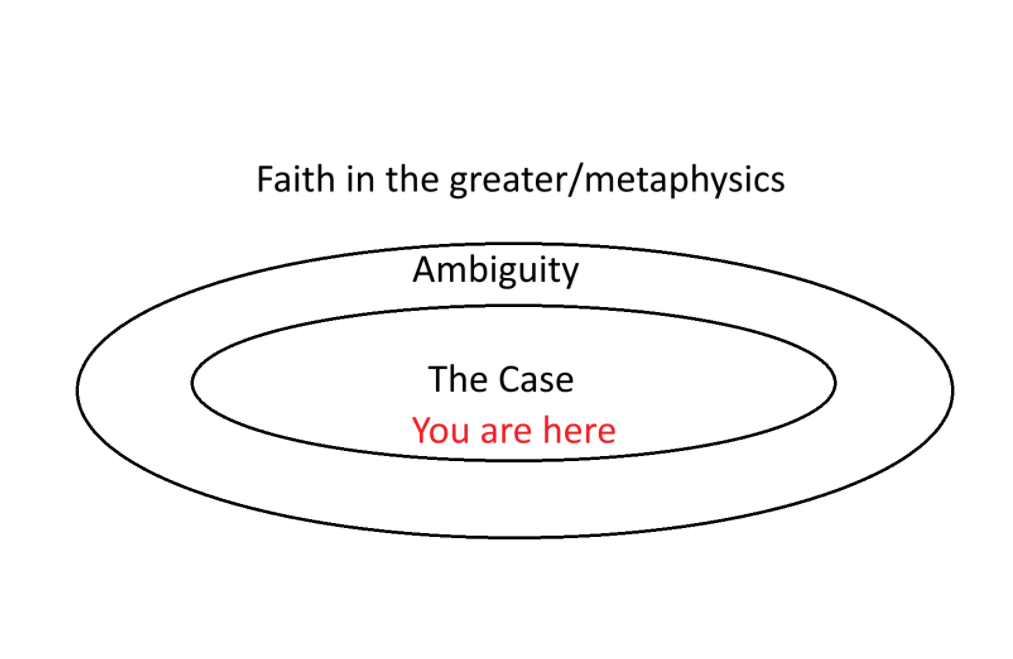

We exist in what I have decided to call the case. This is because of Ludwig Wittgenstein's (Finally some Wittgenstein) famous opening to his 'Tractatus Logico Philosophicus' "The world is everything that is the case". A lot has been said about the Tractatus, it basically goes through the effort of describing the world in painstaking detail via logical propositions, only to at the end say that it is all nonsense. This claim is supported by prior claims that in retrospect would indeed be nonsense. I do think that Wittgenstein is right to say that his logical description of the world is nonsense for it tries to say what cannot be said. For Wittgenstein the world is comprised of language. No nonsense has ever been truer. When we try to use language to describe what is beyond the world, we are only pointing towards what we are trying to say but failing accurately display the whole concept. The world is comprised of language because everything that is the case is us building our world via communicating what is the case to us in our heads. This is why I think it is so important to go through the effort of actually trying to communicate your thoughts even if they are in hindsight not what you wanted; you will get better through practice. What may be the case to me is not necessarily the case to you. The world is just use communicating our cases to each other to collectively contribute to a greater case where we can get closer to the idea of a greatest case. Although we cannot know if we are truly communicating properly as we do not know what is in each others heads, it is contextually for living, useful to assume such. We can make assumptions in the case because it is all contextual for utility. We are following the form of an idea.

Frantz Fanon discussed Hegel's idea of the tri-part soul in that when Fanon was called a racial slur on the bus his soul was split into three; Fanon's own view of himself, how the person who called him the slur viewed him, and the greater view of the scene as a whole. All three views conflict causing Fanon to explode into pieces that he must put back to together later. This is your case conflicting with another's, it can be heart breaking to realize that you may not be seen in the greater case of the many, or even just one individuals case. Fanon is saved by the fact that the world is ambiguous and this is just the case of the white man, not his own or his peers. Fanon is still struggling under the pressure of constant conflicts with what is the case to him compared to others, but he is able to continue living. This is why understanding ambiguity is important, it allows us to not be suffocated by the mountain of a world that has come before us, essentially taking our autonomy.

Now we come back to Kant (I know, but this time we are criticizing him). Kant left us in a place where the phenomenal world and noumenal world exist simultaneously both giving an explanation for the world but saving us from resorting to dogmatism or scepticism. Kant says that faith in the noumena and understanding the phenomenal allows us to have balance. John McDowell discusses this using Kant's framework, but he finds the conclusion of balancing to be intolerable. If you envision dogmatism and scepticism to be on either side of a see saw, and you put yourself in the middle, you would be in the position Kant leaves us in. McDowell says that the see saw is why we are so often confused constantly being brought to either side. One misstep will cause you to fall to the other side, balance is exhausting. McDowell says that the see saw is cemented into the ground by things like institutional norms, biomechanics, and other things that are almost hardcoded into our universal case at this point. When clouded by these conflicting features of our case, how are we supposed to balance without falling. McDowell is also suggesting we take ambiguity into account to see past these all these conflicting perspectives that cloud our vision. Now we can see that it is all contrived, yet we are still lost in ambiguity. As stated before McDowell find living in both phenomena and noumena intolerable with us constantly being driven to dogma or scepticism. McDowell's solution is to get off the see saw, but how is this better than full ambiguity? McDowell suggests what is essentially Aristotle's virtue as a means to cultivate an intentional life where you are free from the pull of either side. McDowell think this because he thinks that we must engage in bildung (cultivating education) to continue to open up our world. Our ability to cultivate education is what McDowell thinks separates us from animals. We have the ability to realize the ambiguity and build on top of it. McDowell believes we exist in a sort of gradient of living where the bottom might be a single celled organism, whereas a cat would be far higher up, because it can learn and cultivate education to a certain point and humans exist at pretty much the top, at least on earth. This is all important because McDowell uses Marx's terminology to say that our alienation from the means of production, with production being our ability to take the world around us and do something with it is what decides this gradient. If you take away our means of production by trapping us in a place where we are subservient to dogma, scepticism, or anything that blocks us from autonomously being able to create from the world around us takes us to the level of animals. We are demi-gods, half animal, half god (not God, that's for later). If a god, as Greek mythology suggests, is a pure concept personified, we are animals that have the abilities to channel these pure concept to create a reality where be are not acting purely on immediate stimuli, then we would fit this description, and it explains why we are so constantly conflicted.

I think I'm done for right now but I have more, the rest is essentially that our faith in the metaphysical is what makes it real for us, and we are able to take pure ideas and follow them to build on top of the ambiguity, to realize our enlightenment. As Jan Zwicky puts it in her 'what is lyric philosophy', truth is like an asymptote approaching infinity. If we are the asymptote and we can see the end point of infinity, we strive to go towards it although we know that we will never actually reach infinity.

Oh yeah! I almost forgot about the actual forms! Everything has a form in the metaphysical, we must respect that form and follow it to get to a place where we can actually do something without babbling incoherently. In the case which is created through translation of thought into a form of language that can be used to contribute to the greater case, you must learn how to not babble incoherently. Your independent case is fine and dandy, but if no one else understands it, what is the point? The more we bildung, the more we are able to see the form clearly and it is why it seems like some people are able to break form and it works for them, but they just have such a good understanding that they have brought a new, never before seen level of the true form into the collective case.